Oracle's Vision Turns Thirty

Oracle’s Vision, the monumental black sculpture located at the intersection of High and Fountain in downtown Springfield, recently celebrated its thirtieth birthday! Over the past three decades, this sculpture has gone from controversial icon of modernism to near obscurity and indifference. During recent research on the piece, I had a number of people quizzically ask, "What monumental sculpture?" I would reply, "The one you walk and drive past everyday." Its history is quite fascinating.While Springfield began reshaping the culture and character of downtown the early-1950s, this "renewal" of the urban core picked up steam in the mid-1970s with the Core Renewal Commission. Between 1974 and 1981, Springfield hired Chicago architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) to design and build four downtown buildings. The current City Hall was the third of these commissions. SOM designed the building in 1977 and it was completed in 1979. While quite radical, especially when compared with the building it replaced, the people of Springfield seemed to love their new modern building. Employees loved the open nature of the building, citizens love the plaza, and vagrants loved the shelter provided by the massive breezeway.

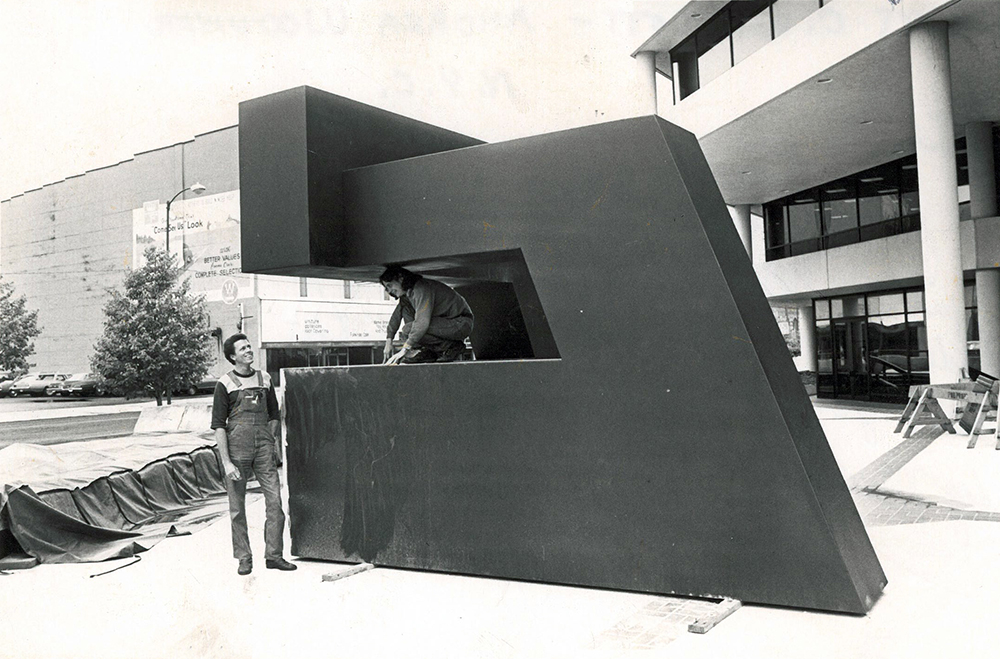

Then, two years later, in the midst of the 1981 recession came Oracle’s Vision. The sculptor was Ronald Bladen, a Canadian born artist then residing in New York City. Bladen, who was selected by a panel comprising members of the National Endowment for the Arts and local citizens, was recognized nationally for his monumental geometric sculptures and is considered to be a founding father of Minimalism. He is perhaps best known for “The X”, which overwhelmed the interior of the Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC in a famous 1967 exhibit. He stated that he wanted his works to have “presence.” Bladen visited Springfield and the new City Hall before submitting his initial design titled Black Lightning. Commissioner Carol Goettman said, “It really looked like a streak of black metal. It seemed to us to be a sort of threatening piece. It didn’t evoke the feeling we wanted.” In the end, Seattle accepted Black Lightning, which is on permanent display at the foot of the Space Needle. Bladen’s second attempt was Oracle’s Vision. He described the piece as an “abstract resolution of form that presents a visual siting in keeping with an open building and plaza.” Some say that Oracle’s Vision symbolizes Springfield's past and its future. If one looks through the window to the southwest, you see the magnificent former City Hall and Myers' Market. Looking northeast, you see the new City Hall and Credit Life Tower.

Workers installing Oracle's Vision in 1981 (Springfield News-Sun)

It was immediately apparent that the sculpture did not have many fans. In an editorial, the Springfield News-Sun stated, “If the Russians decide to invade us, this could be the safest city in the United States. Take that piece of abstract art, for example. You could mount a cannon on it. You could put wheels under it and make it a tank. As a last resort, you could melt it down and make cannon balls.” One man said, “I think when I first saw it, I didn’t really know what it was. I’m not an art lover; consequently I’m not impressed. It certainly isn’t worth $80,000.” Leland Schuler, then a City Commissioner, said that the sculpture “detracts from the beauty of the [recently completed] city building.”

A couple days before the dedication, film actor Vincent Price was in town and became the sculpture's most famous promoter. He said, “I really love it (…) It’s a useful piece of sculpture [and complements the] overall pattern of the building and its environment.” He went on to say, it “could eventually be interpreted as a symbol of our time.” As Price was contemplating the work, the newspaper noted that “several children ran up to it, smiling and laughing, to marvel, to feel its texture and its presence.” Price exclaimed, “Look at those kids, they love it.” The work was immediate and accessible. This, unfortunately, is no longer true. Officials at the city have tried on two separate attempts to move Oracle’s Vision. Bladen, whose contract gave him final approval on all moves, rejected the first attempt just four months after it was installed and died in 1988 during their final attempt. Finally, in 1995, the City hired a local architect to soften its edges. The result deadened the work’s presence by severing its connection with the viewer.

A 1981 News-Sun editorial said, “We’ll all get used to it. Who knows, 20 years from now maybe somebody will wonder how the city was able to get something like that at such a minor cost.” This October marked thirty years. If the orientation of a nearby bench, which faces away from the work, is any indicator, Oracle's Vision is still waiting for that appreciation.